Joseph Whitworth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Joseph Whitworth, 1st Baronet (21 December 1803 – 22 January 1887) was an English

Whitworth received many awards for the excellence of his designs and was financially very successful. In 1850, then a President of the

Whitworth received many awards for the excellence of his designs and was financially very successful. In 1850, then a President of the

He was elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1857, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1857. A strong believer in the value of technical education, Whitworth backed the new Mechanics' Institute in Manchester (later

In January 1887 at the age of 83, Sir Joseph Whitworth died in

In January 1887 at the age of 83, Sir Joseph Whitworth died in

Whitworth also designed a large rifled breech-loading gun with a bore, a projectile and a range of about . The spirally-grooved projectile was patented in 1855. This was rejected by the British Army, who preferred the guns from

Whitworth also designed a large rifled breech-loading gun with a bore, a projectile and a range of about . The spirally-grooved projectile was patented in 1855. This was rejected by the British Army, who preferred the guns from

engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

, entrepreneur, inventor and philanthropist. In 1841, he devised the British Standard Whitworth system, which created an accepted standard for screw threads. Whitworth also created the Whitworth rifle

The Whitworth rifle was an English-made percussion rifle used in the latter half of the 19th century. A single-shot muzzleloader with excellent long-range accuracy for its era, especially when used with a telescopic sight, the Whitworth rifle ...

, often called the "sharpshooter

A sharpshooter is one who is highly proficient at firing firearms or other projectile weapons accurately. Military units composed of sharpshooters were important factors in 19th-century combat. Along with " marksman" and "expert", "sharpshooter" ...

" because of its accuracy, which is considered one of the earliest examples of a sniper rifle

A sniper rifle is a high-precision, long-range rifle. Requirements include accuracy, reliability, mobility, concealment and optics for anti-personnel, anti-materiel and surveillance uses of the military sniper. The modern sniper rifle is a por ...

.

Whitworth was created a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

in 1869. Upon his death in 1887, Whitworth bequeathed much of his fortune for the people of Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, with the Whitworth Art Gallery

The Whitworth is an art gallery in Manchester, England, containing about 55,000 items in its collection. The gallery is located in Whitworth Park and is part of the University of Manchester.

In 2015, the Whitworth reopened after it was transfo ...

and Christie Hospital

The Christie Hospital in Manchester, England, is one of the largest cancer treatment centres in Europe. It is managed by The Christie NHS Foundation Trust.

History

The hospital was established by a committee under the chairmanship of Richard Ch ...

partly funded by Whitworth's money. Whitworth Street

Whitworth Street is a street in Manchester, England. It runs between London Road ( A6) and Oxford Street ( A34). West of Oxford Street it becomes Whitworth Street West, which then goes as far as Deansgate ( A56). It was opened in 1899 and is ...

and Whitworth Hall

The Whitworth Building is a grade II* listed building on Oxford Road and Burlington Street in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, England. It has been listed since 18 December 1963 and is part of the University of Manchester. It lies at the south- ...

in Manchester are named in his honour.

Whitworth's company merged with the W.G. Armstrong & Mitchell Company to become Armstrong Whitworth

Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Co Ltd was a major British manufacturing company of the early years of the 20th century. With headquarters in Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne, Armstrong Whitworth built armaments, ships, locomotives, automobiles and ...

in 1897.

Biography

Early life

Whitworth was born in John Street,Stockport

Stockport is a town and borough in Greater Manchester, England, south-east of Manchester, south-west of Ashton-under-Lyne and north of Macclesfield. The River Goyt and Tame merge to create the River Mersey here.

Most of the town is within ...

, Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

, where the Stockport Courthouse is today. The site is marked by a blue plaque on the back wall of the courthouse. He was the son of Charles Whitworth, a teacher and Congregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

minister, and at an early age developed an interest in machinery. He was educated at Idle

Idle generally refers to idleness, a lack of motion or energy.

Idle or ''idling'', may also refer to:

Technology

* Idle (engine), engine running without load

** Idle speed

* Idle (CPU), CPU non-utilisation or low-priority mode

** Synchronous ...

, near Bradford

Bradford is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Bradford district in West Yorkshire, England. The city is in the Pennines' eastern foothills on the banks of the Bradford Beck. Bradford had a population of 349,561 at the 2011 ...

, West Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire is one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county County of York, West Riding (the area under the control of West Riding County Council), abbreviated County ...

; his aptitude for mechanics became apparent when he began work for his uncle.

Career

After leaving school Whitworth became anindentured

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

to his uncle, Joseph Hulse, a cotton spinner at Amber Mill, Oakerthorpe

Oakerthorpe is a village in Derbyshire, England.

History

Oakerthorpe is a small village near Alfreton. It was known in ancient times as Ulkerthorpe. It lies in the parish of South Wingfield, eleven miles south of Chesterfield in the county of D ...

in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

. The plan was that Whitworth would become a partner in the business. From the outset he was fascinated by the mill's machinery and soon he mastered the techniques of the cotton spinning industry but even at this age he noticed the poor standards of accuracy and was critical of the milling machinery. This early exposure to the mechanics of the industry forged in him the ambition to make machinery with much greater precision. His apprenticeship at Amber Mill lasted for a four-year term after which he worked for another four years as a mechanic in a factory in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

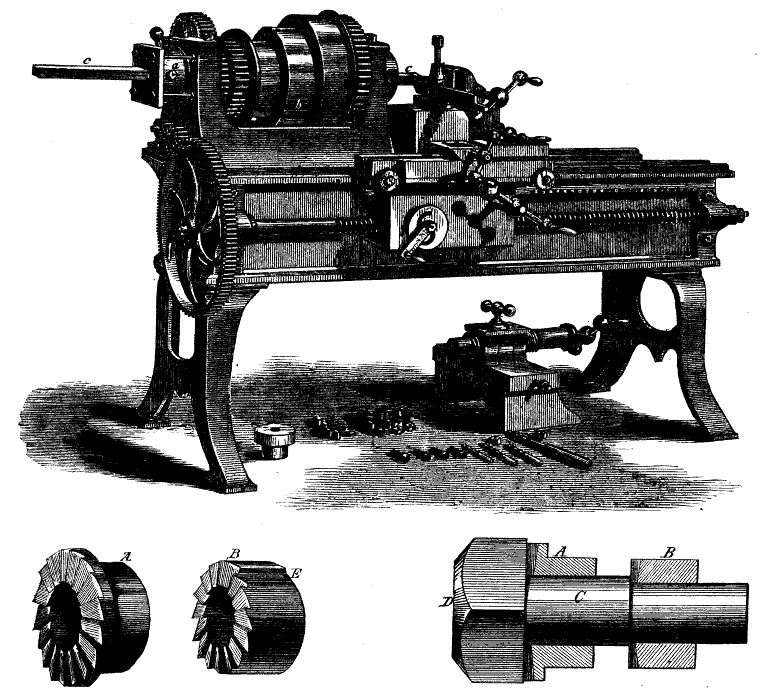

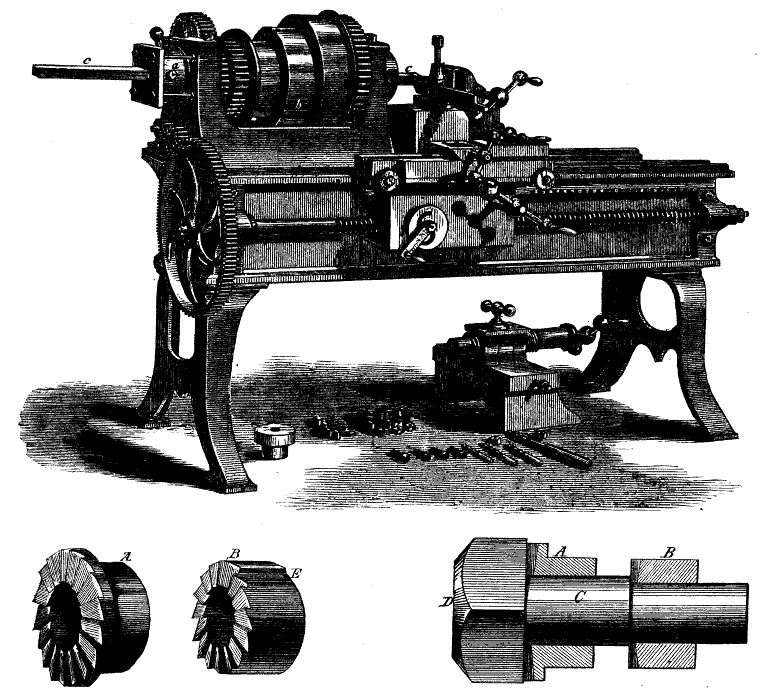

. He then moved to London where he found employment working for Henry Maudslay

Henry Maudslay ( pronunciation and spelling) (22 August 1771 – 14 February 1831) was an English machine tool innovator, tool and die maker, and inventor. He is considered a founding father of machine tool technology. His inventions were ...

, the inventor of the screw-cutting lathe

A screw-cutting lathe is a machine (specifically, a lathe) capable of cutting very accurate screw threads via single-point screw-cutting, which is the process of guiding the linear motion of the tool bit in a precisely known ratio to the rotatin ...

, alongside such people as James Nasmyth

James Hall Nasmyth (sometimes spelled Naesmyth, Nasmith, or Nesmyth) (19 August 1808 – 7 May 1890) was a Scottish engineer, philosopher, artist and inventor famous for his development of the steam hammer. He was the co-founder of Nasmyth, ...

(inventor of the steam hammer) and Richard Roberts.

Whitworth developed great skill as a mechanic while working for Maudslay, developing various precision machine tools and also introducing a box casting scheme for the iron frames of machine tools that simultaneously increased their rigidity and reduced their weight.

Whitworth also worked for Holtzapffel & Co (makers of lathes used primarily for ornamental turning Ornamental turning is a type of turning, a craft that involves cutting of a work mounted in a lathe. The work can be made of any material that is suitable for being cut in this way, such as wood, bone, ivory or metal. Plain turning is work executed ...

) and Joseph Clement

Joseph Clement (13 June 1779 – 28 February 1844) was a British engineer and industrialist, chiefly remembered as the maker of Charles Babbage's first difference engine, between 1824 and 1833.

Biography

Early life

Joseph Clement was born on ...

. While at Clement's workshop he helped with the manufacture of Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

's calculating machine, the Difference engine

A difference engine is an automatic mechanical calculator designed to tabulate polynomial, polynomial functions. It was designed in the 1820s, and was first created by Charles Babbage. The name, the difference engine, is derived from the method ...

. He returned to Openshaw,

Manchester, in 1833 to start his own business manufacturing lathe

A lathe () is a machine tool that rotates a workpiece about an axis of rotation to perform various operations such as cutting, sanding, knurling, drilling, deformation, facing, and turning, with tools that are applied to the workpiece to c ...

s and other machine tools, which became renowned for their high standard of workmanship. Whitworth is attributed with the introduction of the thou

The word ''thou'' is a second-person singular pronoun in English. It is now largely archaic, having been replaced in most contexts by the word '' you'', although it remains in use in parts of Northern England and in Scots (). ''Thou'' is the ...

in 1844. In 1853, along with his lifelong friend, artist and art educator George Wallis

George Wallis (1811–1891) was an artist, museum curator and art educator. He was the first Keeper of Fine Art Collection at South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria & Albert Museum) in London.

Early years

George Wallis, son of John Wal ...

(1811–1891), he was appointed a British commissioner for the New York International Exhibition. They toured around industrial sites of several American states, and the result of their journey was a report 'The Industry of the United States in Machinery, Manufactures and Useful and Applied Arts, compiled from the Official Reports of Messrs Whitworth and Wallis, London, 1854.'

Whitworth received many awards for the excellence of his designs and was financially very successful. In 1850, then a President of the

Whitworth received many awards for the excellence of his designs and was financially very successful. In 1850, then a President of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) is an independent professional association and learned society headquartered in London, United Kingdom, that represents mechanical engineers and the engineering profession. With over 120,000 member ...

, he built a house called 'The Firs' in Fallowfield

Fallowfield is a suburb of Manchester, England, with a population at the 2011 census of 15,211. Historically in Lancashire, it lies south of Manchester city centre and is bisected east–west by Wilmslow Road and north–south by Wil ...

in south Manchester designed by Edward Walters

Edward Walters (December 1808, in Fenchurch Buildings, London – 22 January 1872, in 11 Oriental Place, Brighton) was an English architect.

Life

Walters was the son of an architect who died young. He began his career in the office of Isaac Cla ...

. In 1854 he bought Stancliffe Hall in Darley Dale

Darley Dale, also known simply as Darley, is a town and civil parish in the Derbyshire Dales district of Derbyshire, England, with a population of 5,413. It lies north of Matlock, on the River Derwent and the A6 road. The town forms part ...

, Derbyshire and moved there with his second wife Louisa in 1872. He supplied four six-ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

blocks of stone from Darley Dale quarry, for the lions of St George's Hall in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

. He was conferred with Honorary Membership of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland

The Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland (IESIS) is a multi-disciplinary professional body and learned society, founded in Scotland, for professional engineers in all disciplines and for those associated with or taking an interes ...

in 185He was elected a List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1857, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1857. A strong believer in the value of technical education, Whitworth backed the new Mechanics' Institute in Manchester (later

UMIST

The University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST) was a university based in the centre of the city of Manchester in England. It specialised in technical and scientific subjects and was a major centre for research. On 1 Oct ...

) and helped found the Manchester School of Design. In 1868, he founded the Whitworth Scholarship for the advancement of mechanical engineering. He donated a sum of £128,000 to the government in 1868 (approximately £6.5 million in 2010) to bring "science and industry" closer together and to fund scholarships. In 1869, Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

made Whitworth a baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

.

Scholarships

The Whitworth Scholarship programmes still exist today with 10-15 scholarships being awarded each year. The scholarships are directed at outstanding engineers, like Sir Joseph Whitworth, who have excellent academic and practical skills and the qualities needed to succeed in industry, who are wishing to embark/or have already commenced on an engineering degree-level programme of any engineering discipline. As of 2018, the Scholarship pays up to £5,450 per year for up to four years in the case of a full time undergraduate. The scholarship fund is still that provided from Sir Joseph originally in 1868. The handling and administration of the awards is now carried out by theInstitution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) is an independent professional association and learned society headquartered in London, United Kingdom, that represents mechanical engineers and the engineering profession. With over 120,000 member ...

. Since 2006, a Whitworth Senior Scholarship was agreed by the trustees to support Postgraduate Research leading to a MPhil, PhD or EngD

The Doctor of Engineering, or Engineering Doctorate, (abbreviated DEng, EngD, or Dr-Ing) is a degree awarded on the basis of advanced study and a practical project in the engineering and applied science for solving problems in the industry. In th ...

.

Whitworth Society

In 1923, theWhitworth Society

The Whitworth Society was founded in 1923 by Henry Selby Hele-Shaw, then president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Its purposes are to promote engineering in the United Kingdom, and more specifically to support all Whitworth Scholars ...

was founded by Prof. Hele-Shaw FRS, then president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE) is an independent professional association and learned society headquartered in London, United Kingdom, that represents mechanical engineers and the engineering profession. With over 120,000 member ...

to support all Whitworth Scholars and to promote engineering in the UK. The Society brings together those Whitworth Scholars who have benefited from Sir Joseph Whitworth's generosity.

Death

In January 1887 at the age of 83, Sir Joseph Whitworth died in

In January 1887 at the age of 83, Sir Joseph Whitworth died in Monte Carlo

Monte Carlo (; ; french: Monte-Carlo , or colloquially ''Monte-Carl'' ; lij, Munte Carlu ; ) is officially an administrative area of the Principality of Monaco, specifically the ward of Monte Carlo/Spélugues, where the Monte Carlo Casino is ...

where he had travelled in the hope of improving his health. He was buried at St Helen's Church, Darley Dale

Darley Dale, also known simply as Darley, is a town and civil parish in the Derbyshire Dales district of Derbyshire, England, with a population of 5,413. It lies north of Matlock, on the River Derwent and the A6 road. The town forms part ...

, Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

. A detailed obituary was published in the American magazine ''The Manufacturer and Builder''. He directed his trustees to spend his fortune on philanthropic projects, which they still do to this day. One of the most prominent forms of his generosity was his development of the Whitworth Scholarships with the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Still running to this day, this provides financial opportunities for young engineers with a strong blend of academic and practical abilities. Part of his bequest was used to establish the Whitworth Art Gallery, now part of the University of Manchester, and part went to construct the Whitworth Institute in Darley Dale

Darley Dale, also known simply as Darley, is a town and civil parish in the Derbyshire Dales district of Derbyshire, England, with a population of 5,413. It lies north of Matlock, on the River Derwent and the A6 road. The town forms part ...

.

Memorials

Richard Copley Christie

Richard Copley Christie (22 July 1830 – 9 January 1901) was an English lawyer, university teacher, philanthropist and bibliophile.

He was born at Lenton in Nottinghamshire, the son of a mill owner. He was educated at Lincoln College, Oxford ...

was a friend of Whitworth's. By Whitworth's will, Christie was appointed one of three legatee

A legatee, in the law of wills, is any individual or organization bequeathed any portion of a testator

A testator () is a person who has written and executed a last will and testament that is in effect at the time of their death. It is any "person ...

s, each of whom was left more than half a million pounds for their own use, 'they being each of them aware of the objects' to which these funds would have been put by Whitworth. They chose to spend more than a fifth of the money on support for Owens College Owens may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Owens Station, Delaware

* Owens Township, St. Louis County, Minnesota

* Owens, Missouri

* Owens, Ohio

* Owens, Virginia

People

* Owens (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Ow ...

, together with the purchase of land now occupied by

the Manchester Royal Infirmary

Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI) is a large NHS teaching hospital in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, England. Founded by Charles White in 1752 as part of the voluntary hospital movement of the 18th century, it is now a major regional and nati ...

. In 1897, Christie personally assigned more than £50,000 for the erection of the Whitworth Hall

The Whitworth Building is a grade II* listed building on Oxford Road and Burlington Street in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, England. It has been listed since 18 December 1963 and is part of the University of Manchester. It lies at the south- ...

, to complete the front quadrangle of Owens College. He was president of the Whitworth Institute from 1890 to 1895 and was much interested in the medical and other charities of Manchester, especially the Cancer Pavilion and Home, of whose committee he was chairman from 1890 to 1893, and which later became the Christie Hospital

The Christie Hospital in Manchester, England, is one of the largest cancer treatment centres in Europe. It is managed by The Christie NHS Foundation Trust.

History

The hospital was established by a committee under the chairmanship of Richard Ch ...

.

The university's Whitworth Art Gallery

The Whitworth is an art gallery in Manchester, England, containing about 55,000 items in its collection. The gallery is located in Whitworth Park and is part of the University of Manchester.

In 2015, the Whitworth reopened after it was transfo ...

(formerly the Whitworth Institute) and adjacent Whitworth Park

Whitworth Park is a public park in south Manchester, England, and the location of the Whitworth Art Gallery. To the north are the University of Manchester's student residences known as "Toblerones". It was historically in Chorlton on Medlock but ...

were established as part of his bequest to Manchester after his death. Nearby Whitworth Park Halls of Residence also bears his name, as does Whitworth Street

Whitworth Street is a street in Manchester, England. It runs between London Road ( A6) and Oxford Street ( A34). West of Oxford Street it becomes Whitworth Street West, which then goes as far as Deansgate ( A56). It was opened in 1899 and is ...

, one of the main streets in Manchester city centre

Manchester City Centre is the central business district of Manchester in Greater Manchester, England situated within the confines of Great Ancoats Street, A6042 Trinity Way, and A57(M) Mancunian Way which collectively form an inner ring road. ...

, running from London Road to the south end of Deansgate. Near 'The Firs' a cycleway behind Owens Park

Owens Park was a large hall of residence located in the Fallowfield district of the city of Manchester, England. The site is owned by the University of Manchester and housed 1,056 students. Owens Park is a significant part of the Fallowfield C ...

is called Whitworth Lane. In Darley Dale is another Whitworth Park. In recognition of his achievements and contributions to education in Manchester, the Whitworth Building on the University of Manchester

, mottoeng = Knowledge, Wisdom, Humanity

, established = 2004 – University of Manchester Predecessor institutions: 1956 – UMIST (as university college; university 1994) 1904 – Victoria University of Manchester 1880 – Victoria Univer ...

's Main Campus is named in his honour.

Work

Accuracy and standardisation

Whitworth popularised a method of producing accurate flat surfaces (seeSurface plate

A surface plate is a solid, flat plate used as the main horizontal reference plane for precision inspection, marking out (layout), and tooling setup. The surface plate is often used as the baseline for all measurements to a workpiece, theref ...

) during the 1830s, using engineer's blue and scraping techniques on three trial surfaces. Up until his introduction of the scraping technique, the same three-plate method was employed using polishing techniques, giving less accurate results. This led to an explosion of development of precision instruments using these flat-surface generation techniques as a basis for further construction of precise shapes.

His next innovation, in 1840, was a measuring technique called "end measurements" that used a precision flat plane and measuring screw, both of his own invention. The system, with a precision of one millionth of an inch (25 nm), was demonstrated at the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary The Crystal Palace, structure in which it was held), was an International Exhib ...

of 1851.

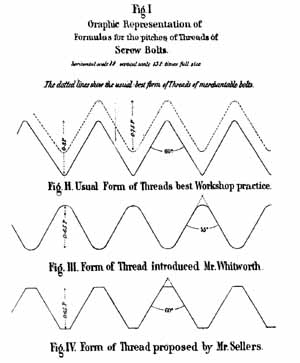

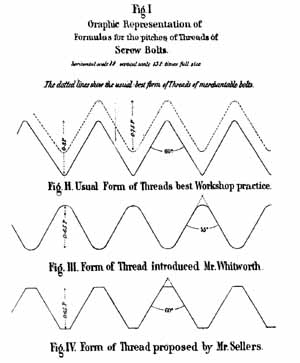

In 1841 Whitworth devised a standard for screw threads with a fixed thread angle of 55° and having a standard pitch for a given diameter. This soon became the first nationally standardised system; its adoption by the railway companies, who until then had all used different screw threads, led to its widespread acceptance. It later became a British Standard

British Standards (BS) are the standards produced by the BSI Group which is incorporated under a royal charter and which is formally designated as the national standards body (NSB) for the UK. The BSI Group produces British Standards under the a ...

, " British Standard Whitworth", abbreviated to BSW and governed by BS 84:1956.

Whitworth rifled musket

Whitworth was commissioned by theWar Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

of the British government to design a replacement for the calibre .577-inch Pattern 1853 Enfield

The Enfield Pattern 1853 rifle-musket (also known as the Pattern 1853 Enfield, P53 Enfield, and Enfield rifle-musket) was a .577 calibre Minié-type muzzle-loading rifled musket, used by the British Empire from 1853 to 1867; after which many wer ...

, whose shortcomings had been revealed during the recent Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

. The Whitworth rifle

The Whitworth rifle was an English-made percussion rifle used in the latter half of the 19th century. A single-shot muzzleloader with excellent long-range accuracy for its era, especially when used with a telescopic sight, the Whitworth rifle ...

had a smaller bore of which was hexagonal, fired an elongated hexagonal bullet and had a faster rate of twist rifling ne turn in twenty inchesthan the Enfield, and its performance during tests in 1859 was superior to the Enfield's in every way. The test was reported in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' on 23 April as a great success. However, the new bore design was found to be prone to fouling and it was four times more expensive to manufacture than the Enfield, so it was rejected by the British government, only to be adopted by the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed For ...

. An unspecified number of Whitworth rifles found their way to the Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

states in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, where they were called "Whitworth Sharpshooters Whitworth Sharpshooters were the Confederates' answer to the Union sharpshooter regiments, and they used the British Whitworth rifle. These men accompanied regular infantrymen and their occupation was usually eliminating Union artillery gun crews. ...

". The rifles were capable of sub-MOA

Moa are extinct giant flightless birds native to New Zealand.

The term has also come to be used for chicken in many Polynesian cultures and is found in the names of many chicken recipes, such as

Kale moa and Moa Samoa.

Moa or MOA may also refe ...

groups at 500 yards.

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

opened the first meeting of the National Rifle Association

The National Rifle Association of America (NRA) is a gun rights advocacy group based in the United States. Founded in 1871 to advance rifle marksmanship, the modern NRA has become a prominent Gun politics in the United States, gun rights ...

at Wimbledon

Wimbledon most often refers to:

* Wimbledon, London, a district of southwest London

* Wimbledon Championships, the oldest tennis tournament in the world and one of the four Grand Slam championships

Wimbledon may also refer to:

Places London

* ...

, in 1860 by firing a Whitworth rifle from a fixed mechanical rest. The rifle scored a bull's eye at a range of .

Whitworth rifled cannon breech-loading artillery

Whitworth also designed a large rifled breech-loading gun with a bore, a projectile and a range of about . The spirally-grooved projectile was patented in 1855. This was rejected by the British Army, who preferred the guns from

Whitworth also designed a large rifled breech-loading gun with a bore, a projectile and a range of about . The spirally-grooved projectile was patented in 1855. This was rejected by the British Army, who preferred the guns from Armstrong Armstrong may refer to:

Places

* Armstrong Creek (disambiguation), various places

Antarctica

* Armstrong Reef, Biscoe Islands

Argentina

* Armstrong, Santa Fe

Australia

* Armstrong, Victoria

Canada

* Armstrong, British Columbia

* Armstrong ...

, but was used in the American Civil War.

While trying to increase the bursting strength of his gun barrels, Whitworth patented a process called "fluid-compressed steel" for casting steel under pressure and built a new steel works near Manchester. Some of his castings were shown at the Great Exhibition in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

ca. 1883.

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Whitworth, Joseph 1803 births 1887 deaths People from Stockport 19th-century British philanthropists American Civil War industrialists Baronets in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom British mechanical engineers Engineers from Lancashire English inventors English philanthropists Fellows of the Royal Society Firearm designers History of Greater Manchester Machine tool builders People associated with the University of Manchester People of the Industrial Revolution Bessemer Gold Medal 19th-century English businesspeople